Our research into how the built environment can support circadian health has yielded practical strategies that designers can apply to new or existing buildings. Download our findings here.

Circadian health—the alignment of the body’s circadian rhythm to the natural day-night cycle—is a critical but underappreciated factor in designing for wellness. Despite spending nearly 90% of our lives indoors, we rarely consider how the design of our spaces can support or disrupt these rhythms. By shaping environments that work with, rather than against, our biology, we can enhance wellbeing in intentional and lasting ways.

Both scientific understanding and mainstream awareness of circadian health has increased over the past decades; popular magazines warn of the sleep disruptions caused by daylight saving time, while products like blue-light-blocking glasses claim to mitigate the effects of straying from the day-night cycle. However, we have lacked specific guidance on how to successfully integrate circadian health into design strategies.

Thanks to a grant from the American Institute of Architects’ Upjohn Research Initiative, a collaborative project from Quinn Evans and the University of Oregon Institute for Health in the Built Environment sheds new light on this critical aspect of wellness.

Why is circadian health important?

Maintaining circadian rhythms on the proper cycle is crucial for human health; poor circadian health is associated with higher rates of obesity, diabetes, and mood and anxiety disorders. Symptoms of circadian rhythm disorders include fatigue, difficulty concentrating, headaches, emotional dysregulation, and impaired judgment—which can negatively impact relationships and work or school performance.

Why is circadian health a design issue?

We believe any aspect of human health that can be influenced by the built environment is a design issue. Morning daylight is one of the most powerful regulators of circadian health, yet most people spend the morning hours inside buildings rather than outdoors. That’s why design matters.

Green building rating systems like LEED have long recognized the importance of daylighting, or bringing natural light to regularly occupied areas, but they tend to emphasize visual comfort and energy performance over providing sunlight at the time of day and view angle where it would have the greatest impact on circadian health. Emerging research makes clear that not all daylight is created equal. Traditional standards rely on metrics such as target illuminance, annual sunlight exposure (ASE), or spatial daylight autonomy (sDA), all of which measure the amount light on a horizontal surface at either one point in time or cumulatively across the year. But circadian health is dependent on qualities of daylight beyond visual acuity, so these standards don’t directly align.

While WELL is one of the few frameworks to address circadian lighting, its metric—equivalent melanopic lux (EML)—is primarily focused on electric light and remains difficult for most projects to model or apply. Designers have needed practical, accessible strategies to bring circadian health into everyday design practice.

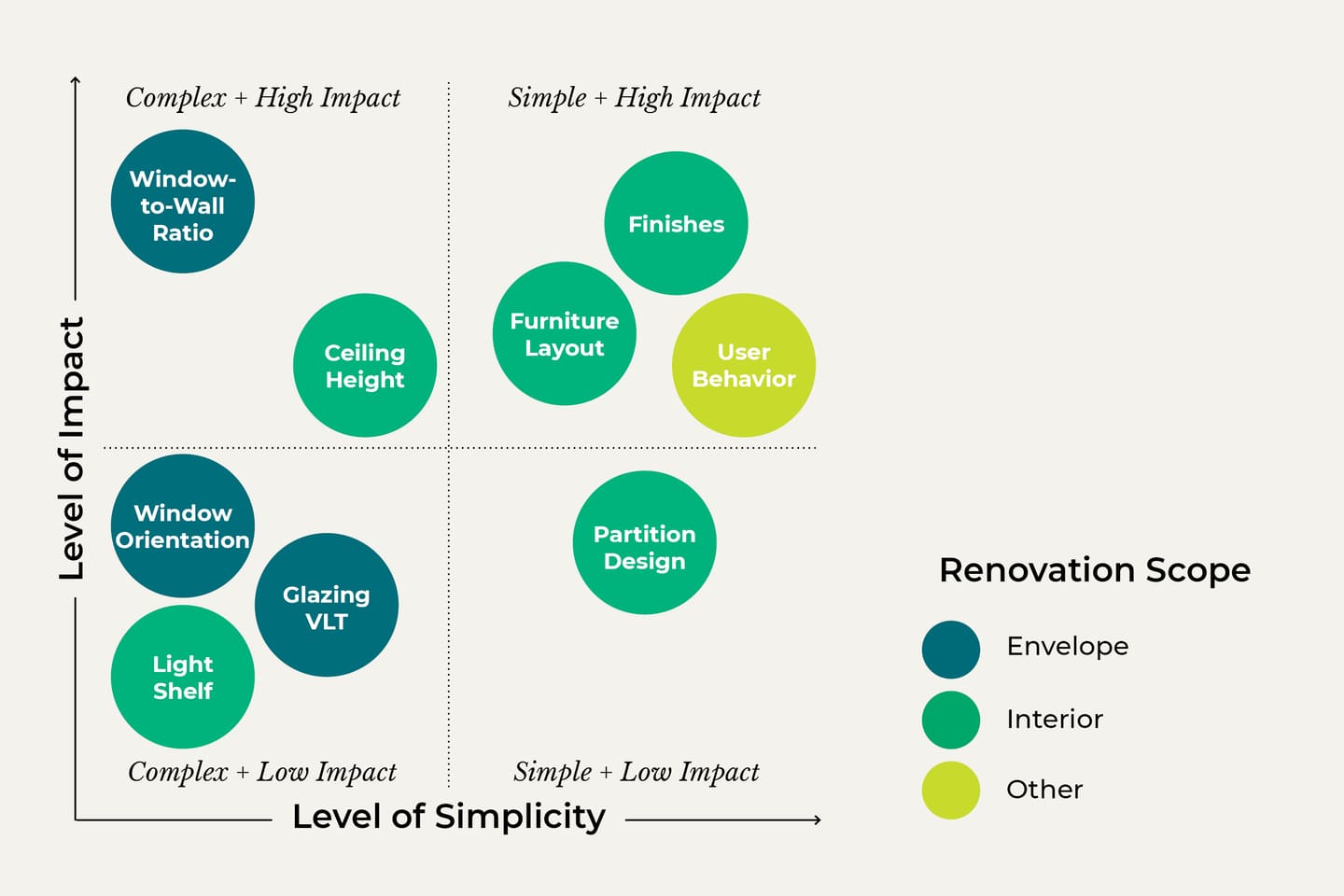

That’s where our research comes in. We wanted to give designers data-backed strategies for improving buildings’ circadian health potential. Furthermore, we wanted to provide guidance that works for both new construction and renovations—because renovations present the additional challenge of working within the constraints of an existing building envelope. Our goal was to find opportunities regardless of project scope or size to make improvements for circadian health.

How can buildings support circadian health?

The short answer is this: Buildings can support circadian health by providing enough daylight at occupants’ eye level in the morning.

Our research partners at the University of Oregon propose a novel metric, spatial melanopic daylight autonomy (smDAEML 150/275/50%), for determining the circadian health potential of a given space. This metric expresses the percentage of workstation positions within the space where the occupant’s view position meets or exceeds 150 equivalent melanopic lux for at least 50% of the time between 9:00am and 1:00pm over the course of a year.

We then tested several design variables via both computer modeling and real-world projects to determine which interventions yielded the most improvement to a space’s smDAEML 150/275/50%. As we expected, increasing the window-to-wall ratio (WWR) had a big impact. However, we were surprised to find that simpler strategies like optimizing furniture layouts and encouraging users to move to better-lit spaces were also very effective. In fact, using light-colored and reflective finishes on walls, ceilings, and floors increased smDAEML 150/275/50% almost as much as a higher WWR.

What’s next?

You can download our full research report, as well as a condensed executive summary and a graphic guide for designers, here. For us, supporting the wellness building occupants is an extension of our mission to discover design solutions that enrich lives. We hope the design community will use and build on our research to create ever-better places for people.

.avif)