THIS POST ORIGINALLY APPEARED AS AN ARTICLE IN THE DECEMBER 2025 ISSUE OF PAPYRUS, THE MAGAZINE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF MUSEUM FACILITY ADMINISTRATORS.

Collections tell a museum’s stories. But what if the building could speak for itself?

Today, museums are using digital twins (models that integrate documentation and real-time performance data into one accessible platform) to understand and manage environmental conditions such as temperature, humidity, and light levels within the building. Tomorrow, digital twins will be doing much more, potentially transforming the museum experience for both operators and visitors.

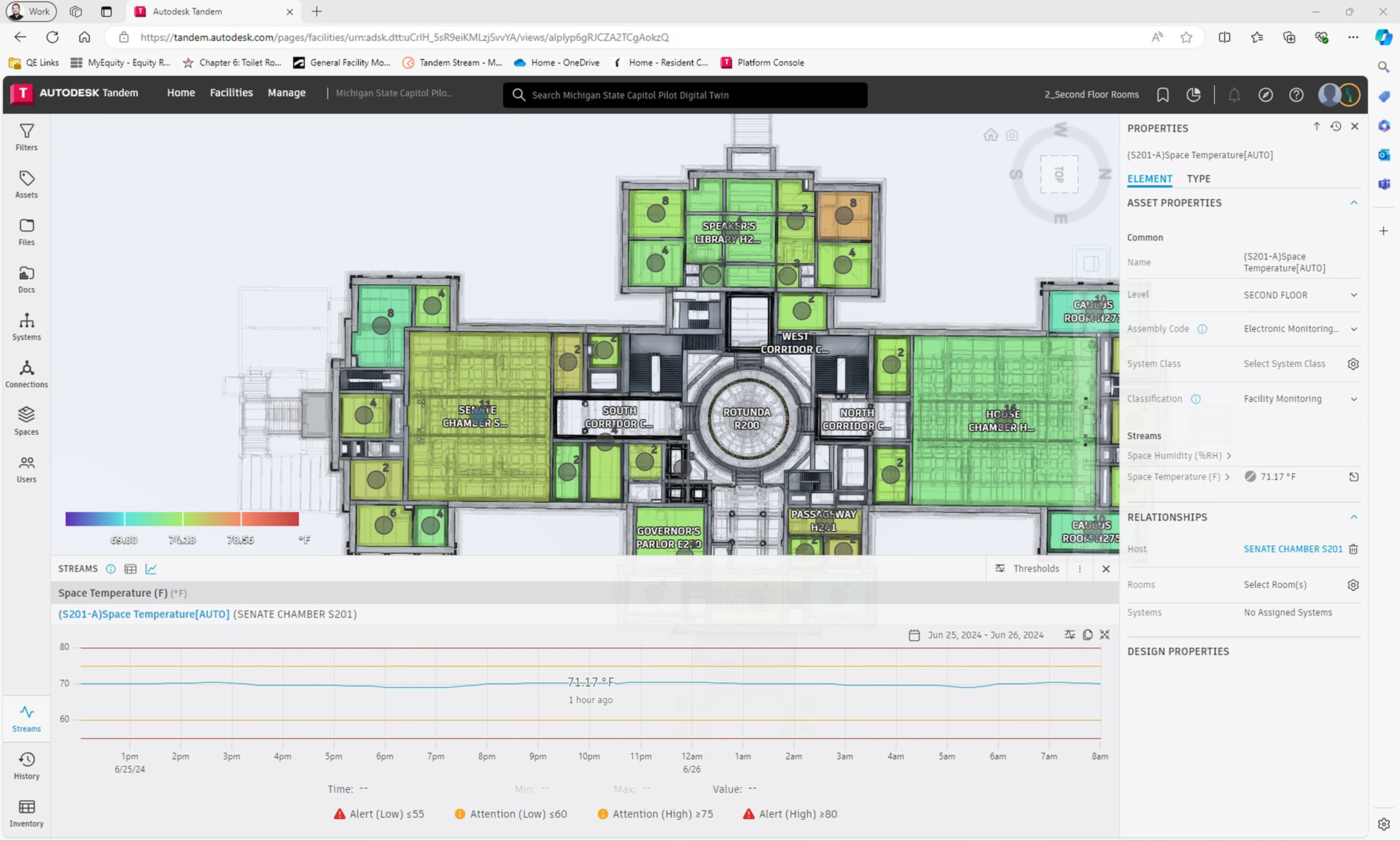

In 2015, my colleagues Alyson Steele and Rob Fink wrote in Papyrus about how George Washington’s Mount Vernon was using Historic Building Information Management (HBIM) as a repository to organize historic documentation. Since then, Quinn Evans has further advanced this concept at the Michigan State Capitol by creating a digital twin of the 1879 building that integrates both historic information and real-time sensor data.

And that is only scratching the surface of the capabilities for digital twins. Because these platforms can synthesize any number of data streams, they have the potential to measure, parse, and optimize many aspects of museum operations. From historic preservation to visitor services, digital twins hold great promise for streamlining the management of cultural facilities.

Ultimately the museum is working towards having a dashboard view of what is happening in the museum at all times, but also have a historic view of how things change. This will allow us to pick up on trends and become a more efficient and sustainable organization.

RICHARD HINTON, CHIEF INFORMATION OFFICER, NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM, LONDON, UK (SOURCE)

What Is a Digital Twin?

At its most basic, a digital twin is a virtual representation of a physical place or object, driven by data. Born out of NASA’s Apollo 13 crisis in 1970, digital twins initially emerged as simulators that mirrored physical systems, to solve problems in real time. In the decades since, the term “digital twin” has become a catch-all for various types of electronic representations.

In museum and heritage contexts, the term is sometimes used to refer to any high-quality electronic replica: the Uffizi Galleries have developed such likenesses for their sculpture collection. Although detailed scans can be very useful (pre-fire point clouds were used to help rebuild Notre-Dame Cathedral), they are a static snapshot in time, and become outdated the moment the object changes.

In this article, “digital twin” is used to mean a virtual model of a facility that integrates both historic and live data to communicate how the physical building is performing. A digital twin requires two foundational elements: an accurate building model, and active data inputs.

A BUILDING INFORMATION MODEL

The core of a twin consists of a 3D building model, typically built using a BIM tool such as Autodesk Revit. The BIM comprises spatial geometry (walls, floors, and ceilings); mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems (ductwork, piping, and equipment); and other building components, such as finishes and materials.

CONTINUOUS DATA

The other component is data, which can be integrated via three methods.

First, parameters can be set up to connect to existing documents and records that are critical to understanding the building’s performance over time. Existing drawings from past renovations, reports detailing the movements of collection items through the facility, and owner’s manuals for essential pieces of equipment: all of these can be linked to their digital counterparts within the twin.

Second, the twin can integrate with existing operational systems that already report status updates on equipment and conditions. Dashboards can present live data from these systems via easily understood graphics, and users can set up automatic alerts when thresholds are exceeded.

Third, Internet of Things (IoT) sensors can be placed throughout the building to capture variables such as temperature, humidity, carbon dioxide, lux, ultraviolet light, vibration, or movement—virtually anything that can be measured can be reflected in the twin.

INTEGRATION

The BIM and data streams are then fed into a digital twin platform (for example, Tandem, iTwin, dTwin, or ArcGIS Indoors). This continuously updates the virtual model to represent the real building’s conditions at any given time, enabling holistic dashboard views and trend analysis.

Note that a digital twin is not intended to replace a Building Management System (BMS), Collections Management System (CMS), or any existing workflow that is vital to a facility’s success. Instead, the twin connects these siloed systems into a unified model, creating a single access point for multiple stakeholders to understand and interact with the information they need, when they need it.

Even for new buildings, developing a digital twin involves effort and strategic planning to extend the design and construction BIM. For existing or historic buildings, however, the process is considerably more complex.

Digital Twins for Historic Buildings

Developing digital twins for historic buildings presents additional challenges and corresponding opportunities, necessitating extra steps to document, interpret, and model conditions that may have evolved over decades or centuries. For one thing, an accurate as-built drawing set for an existing facility is often difficult to come by. Original plans may be missing, incomplete, or superseded by alterations, repairs, or undocumented modifications.

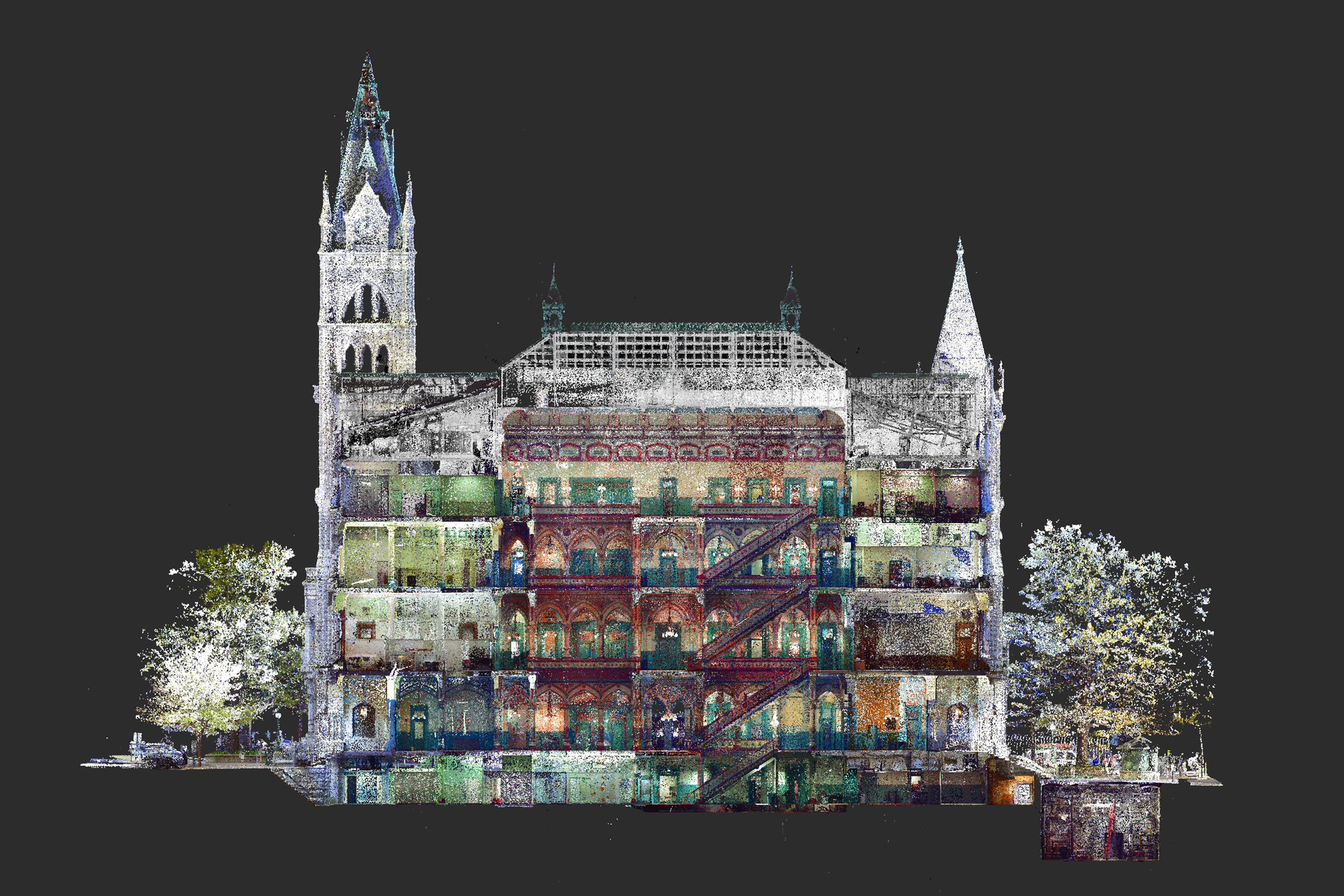

Thus, before a digital twin can be created, the first step is to model the building’s existing conditions. This is typically achieved through a scan-to-BIM process, in which Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) scanning and photogrammetry produce a millimeter-accurate point cloud that serves as the spatial foundation for the model. To complement this data, architects draw upon archival records and conduct on-site surveys and investigations to reconstruct building systems and elements that are hidden within walls, ceilings, and floors.

Once the BIM model is hosted on an accessible online platform and connected to various data streams, it becomes a digital twin. This allows for a single repository to capture a wealth of documentation, such as historic drawings, conservation records, and repair histories. By collocating operational and heritage data within the twin, building stewards gain a unified tool that helps them make decisions efficiently and effectively.

How Museums Are Currently Using Digital Twins

Although digital twins have been created for skyscrapers and large infrastructure projects since the 2010s, the technology is still relatively new to museums. Two examples of cultural facilities that have developed twins are the Natural History Museum in London, UK, and the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit, Michigan. Other museums and cultural sites are utilizing individual components of digital twins—such as BIMs, point clouds, and IoT sensors—in innovative ways that demonstrate additional use cases for digital twins.

FACILITIES MAINTENANCE

Monitoring environmental conditions is a major focus for any museum, so it is no surprise that both the Natural History Museum and The Wright have used their digital twins to create dashboards showing real-time temperature and humidity levels. We have done the same thing for the Michigan State Capitol, which, in addition to art and furniture collections, houses more than nine acres (36,000 square meters) of murals and other decoratively painted surfaces.

All three institutions are using their twins as integrated information hubs that consolidate data on the location, condition, and maintenance history of building systems and equipment. If a leak occurs behind a wall, for instance, facilities staff can pinpoint the affected pipe without resorting to exploratory demolition, saving both time and unnecessary impact on the building.

You try to search and find information that either doesn’t exist, or you spend hours and hours trying to find information that’s just buried somewhere. It creates a lot of challenges, wastes a lot of time.

WARREN EMERSON, DIRECTOR OF FACILITIES, CHARLES H. WRIGHT MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY (SOURCE)

CAPITAL PLANNING AND DESIGN

Digital twins are a rich source of data for capital projects. Mount Vernon’s BIM, which is tagged with documentation on historic materials and assemblies, informed the design of a new fire-suppression system. The team was able to identify areas of lower historic integrity, where components could be inserted without compromising the 18th-century building fabric.

PRESERVATION AND RISK MANAGEMENT

The city of Genoa, Italy, created a digital twin of its historic core, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. IoT sensors collect data on airborne pollutants, helping stewards to understand which sites are most vulnerable, and to prioritize them for conservation. Access to real-time data also allows the city to proactively limit crowding in sensitive areas during periods of high pollution.

At Detroit’s Michigan Central Station, many of the building’s decorative elements were missing, due to decades of deterioration and vandalism. Detailed scans enabled automotive engineers from Ford (the client for the station’s rehabilitation) to extrapolate and replicate missing ironwork, based on remaining fragments.

In a worst-case scenario, comprehensive scans can help a heritage site rebuild after a disaster. Recognizing this potential, the European Commission encourages member states to digitize “all monuments and sites that are at risk of degradation and half of those highly frequented by tourists” by 2030.

THE VISITOR EXPERIENCE

The Wright’s digital twin allows a novel approach to visitor observation. The museum uses carbon dioxide data from sensors throughout the galleries to infer visitor movement patterns and understand which exhibits people are lingering at. The data is inherently anonymized and less invasive than video monitoring or in-person tracking.

Several museums are utilizing high-quality scans or building models to enhance the visitor experience by extending it into the virtual realm. For example, the Kyoto National Museum has developed a model that allows visitors to explore the Meiji Kotokan—a historic space that is closed to the public—through a web interface.

The Deutsches Museum in Munich, Germany, offers an online experience based on a point cloud. It can be used to virtually “visit” the museum, or it can help an in-person visitor navigate the museum, access interactive content, or learn more about a specific collection object. The museum has plans to link IoT sensors to the model to create a true digital twin.

Future Possibilities

The potential of a digital twin is limited only by the amount of data fed into it. Here are just a few of the possibilities we see for museums to further incorporate twins.

COLLECTIONS MANAGEMENT AND CARE

Integrating the CMS into the twin would result in a powerful conservation tool. For example, with an integrated CMS-BMS dashboard, curators could receive an alert when a gallery’s environmental conditions deteriorate, and instantly see which objects may be at risk based on their material properties. Similarly, the incorporation of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) data would enable dashboards showing problem areas over time.

PREVENTIVE MAINTENANCE

By linking a facility’s ticketing system to the twin, leaders could use it to address deferred maintenance. Armed with reports showing equipment that is repeatedly malfunctioning or approaching the end of its useful life, they would be able to request funding for replacements before the existing equipment fails.

SUSTAINABILITY

Museums are notorious energy hogs, due to the imperative to maintain strict environmental conditions. By analyzing factors such as occupancy patterns and the energy consumption of heating and cooling equipment, digital twins can help identify inefficiencies and optimize systems to reduce carbon emissions.

SAFETY AND SECURITY

Linking camera systems and occupancy sensors to the twin would show exactly where people are within the building, in the event of an emergency. On the proactive side, connecting the twin to meteorological models could help leaders anticipate and mitigate risk from severe weather events, or engage in scenario planning for natural disasters.

PERSONALIZED EXPERIENCES

A public interface based on a digital twin could offer visitors a completely tailored museum experience. Answering a few simple questions about their interests and needs could allow a visitor to generate a customized multimedia tour that avoids overcrowded areas—complete with the option to pre-order lunch at the café. CMS records could also be used to inform tour content and enable in-depth exploration of objects that spark interest, thereby strengthening visitor engagement.

The Future Is Now

Ten years ago, when my colleagues wrote in Papyrus about using a BIM to store and organize records related to historic buildings, we were venturing into unexplored territory. Who would have believed that within a decade we would be able to attach live sensor networks and operational intelligence to heritage models?

Yet here we are. The rise of affordable IoT devices has made it increasingly feasible to treat museums as living, monitored systems. At a select number of museums, digital twins are already being utilized to enhance facility operations, inform conservation decision-making, and augment visitor analytics. Over the next decade, we believe that the role of twins will expand to encompass collections management, security, and visitor services—in short, digital twins will become integral tools for museum operations.

Museum buildings have always been keepers of the past. Now, through digital twins, they are also stewards of their own future.